<— 2: Starting a Career 4: Maritime Wireless Company —>

The Automatic Stamping Machine Company Limited

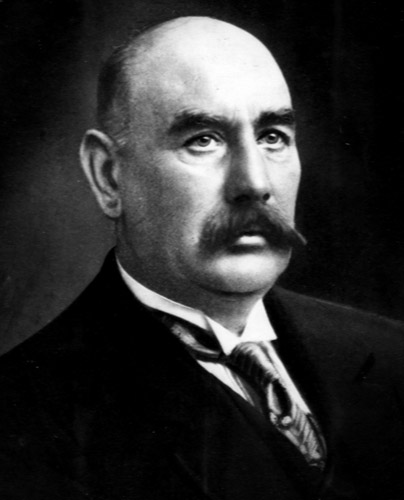

On his return from Lake Tekapo, his good friend Edgar Pannell suggested he consider starting in employment with Mr Ernest Moss, and his company, The Automatic Stamping Machine Company Limited.

Edgar Pannell, who was a brilliant engineer, had been engaged by Mr Moss during the production of the first credit machine and was largely responsible for its design and construction. While Basil was working at the International Exhibition, Edgar had kept in touch with him regarding the development of the Franking Machine.

Basil considered that he would be in good company with his friend as Works Manager, and so, on Edgar Pannell’s advice, Mr Moss gave Basil an immediate start on 30/- per week “and prospects once the company got off the ground”. There were only 3 machines installed in Christchurch at the time, and orders were coming in.

Under the guidance of his friend, Basil made good progress in becoming familiar with the machine and its workings. As the company grew and more hands were taken on, his progress as Edgar’s off-sider was greatly accelerated and he was given more responsibility and fairly frequent 5/- rises.

In 1908, when Basil was 19, the Company decided to try for approval in Australia and he was sent to Melbourne with a franking machine for installation in the Internal Affairs Department in Melbourne. The machine was to be on trial by the Australian Government for 2 months. Basil was instructed to call every morning to see that all was well and to make periodic reports back to the Company in New Zealand. The trial was a complete success but it was turned down by Parliament when it was thought that the impression may have been able to be forged. Naturally this was a big disappointment for the Company, as they were unable at the time, to secure representation to disprove the charge.

While he was in Australia, his father wrote to him with words of advice on how to behave, especially with the opposite sex.

Dear Bas

Write me a line before you leave – that is if you are not coming this way.

I won’t load you up with advice old chap – you know how I would like you to go along. Take that little red book with you and use it and don’t fail to attend the communion service wherever you may be and do not taste alcohol (as promised) and have nothing to do with girls – they are kittle cattle and you will do well to ignore them for a year or two yet until you are in a position to marry. That is my advice at any rate. Be honourable in all things and keep a clean conscience and there is no fear that you will get on. God will see to that.

With best love and wishes always

from your affectionate Dad

On his return to New Zealand, Basil learnt that a Mr Rickard had been appointed Final Tester of the machines before installation. He was a friend of Mr Moss. Unfortunately for Mr Rickard, he let one machine through with the meter reading £20. For this, Mr Moss hit the proverbial roof, and sacked him on the spot. Basil was offered and accepted the vacated position with mixed feelings. He knew that, with one error in the final testing, he would be “out and subject to a similar fate as Rickard’s.”

“To protect myself against the likelihood of such a happening,” Bas later explained, “I devised a system whereby the Postal Official had to sign my register that the machine was sealed at absolute zero, when delivered to the purchaser. Thus was solved another problem, for never was the error repeated during my employment with the company, and where my name was registered as Final Tester.”

The following appears on the Museum of New Zealand website:

Moss Machine No. 2 automatic stamp franking machine

Moss franking machines were at the leading edge of postal technology during the Edwardian period, enabling the quick and efficient stamping of large volumes of mail for businesses.

New Zealand engineer Ernest Moss invented ‘Moss Machine No. 1’ in about 1904, followed quickly by ‘Moss Machine No. 2’. Moss No. 2 was the first machine to be used in New Zealand by a business (the Christchurch Meat Company). A sovereign coin dropped in the slot allowing 240 frankings of 1d denominations for standard letters.

Upon the success of the product, Messrs Moss and Dombrain formed The Automatic Stamping Company which later became the The Automatic Franking Machine Company. The Post and Telegraph Department gave them a licence to construct the machines and lease them to businesses.

When Ernest Moss died in 1932, the Evening Post newspaper wrote that his automatic postal franking machine ‘was recognised by the World Postal Union, and has done more for the postal systems of the world than anything conceived in that realm since Rowland Hill first proposed penny postage’ (20 April 1032, p. 7).

Basil was engaged in the manufacture of franking machines for 13 years, finally graduating to the position of Chief Inspector for New Zealand.

Travelling Representative

As time went by, and after several 5/- rises, Basil was promoted to the position of Travelling Representative, which covered the inspection of all machines installed in capital and country centres and, where necessary, an overhaul and the fitting of new parts. For this purpose he carried a letter of introduction from the Postmaster General’s Department which requested each and every postmaster to afford him every assistance in carrying out this work.

Sometimes this work was carried out in a hotel bedroom, and in the cities it was necessary to hire a Sample Room from the New Zealand Express Company where there would be a number of machines for attention and where he could work in peace and be free of interruption.

He would be away for several weeks at a time and periodical reports had to be forwarded to the Company as to progress. Each and every six months these inspections would be carried out and he covered the whole of New Zealand in doing so, particularly the North Island, where most of the machines were installed.

At various times the Postal Department would communicate with the Company which can best be described as a “scare letter”. It would be to the effect that someone had produced a facsimile of the Frank Die and “what did the Company propose to do about if?” There were many instances of this over the years with the pattern being always the same.

Mr Moss would show me the letter and a copy of the forgery – I would take the original print of the die supposedly forged (which, unknown to other than the Company, carried secret markings) and the forgery easily detected. Armed with this, I had to dash home, grab my pyjamas and toothbrush, and catch the evening ferry steamer to Wellington. Upon arrival I would attend the Department where arrangements would be made to compare the impressions they were holding. With the knowledge of the secret markings in the original die, I was ready for the test. There would be a number of officials present and I would be seated on one side of the table. I was handed a bundle of envelopes and requested to to throw the forgeries on one side and the genuine on the other. The speed with which I could separate the forgery from the genuine would be enough to impress the audience and with this in mind, I started. To say they were convinced would be an understatement. Another 5/- rise.

By 1910 Basil was known as the Company’s Trouble Shooter and Technical Expert and it was always his job to sort out any trouble which may have developed with the operation of a machine, more particularly with the registration of the meter and where it was said to be out of balance with the postage book.

It can be said here that the Credit Meter was always 100% reliable and correct, and that any question as to its fault was always found to be due to misuse of the Value Indicator being left in a higher slot.

It was early in 1912 that Basil was in Wellington for the purpose of fitting another fraud-prevention device to all the franking machines in that city, for which the Postal Department was really “on the warpath”. He had completed well over 100 machines when he was advised by telegram that the Auckland users were about to hold an “indignation meeting” regarding the delay in having their machines returned. The Department had “jumped the gun” and withdrawn all the machines without notifying the Company. The telegram read:

“It is imperative that you should proceed to Auckland without delay- as owners of machines there are getting impatient and we will shortly be ‘up against’ the Department if this work is not gone on immediately. We must say that we have received a telegram from Auckland advising that the users are holding an indignation meeting on Thursday – STOP – You will thus see that the need for haste is most urgent.”

Basil left immediately for Auckland. [further info re-problem if needed]

On September 4 Basil arrived in Auckland, heralded in the Star newspaper as “an expert from the south [who] would be in Auckland for the purpose of inspecting the machines.” When he arrived he was greeted by “a mountain of machines to be attended and stacked in the post office.”

“My first move was to hire a Sample room from the NZ Express Company and have the machines removed thereto, and where I could make my arrangements to get cracking, for I was the Southern Expert and the villain in the piece. . .1 worked night and day to get the work completed and when the great day arrived, never will I forget the feeling of satisfaction that it gave to realise that peace was once again restored and I could go my way.”

Basil returned to Christchurch and on the way visited several smaller towns to make the fitment. On his return he recommenced his job as tester.

He spoke to Mr Moss about the new machines that had been reported as landing in Australia. Mr Moss got him a position at the Maritime Wireless Company Ltd at Randwick. This company had just installed £30,000 worth of the latest equipment from America.

After spending valuable time in Australia a homesick Basil returned home later in 1914, married Elsie Maud Wright, and recommenced work for Mr Moss, continuing to work there until the declaration of war sometime later.

<— 2: Starting a Career 4: Maritime Wireless Company —>

Edgar Pannell is mentioned in the book ‘Aranui and Wainoni History’ by Timothy Baker, which has a short section on the Pannell family.

A search on a family tree website reveals that the NZ World War I Army Casualty List says that Edgar was wounded on 12th June 1917, whilst the NZ World War I Army Roll of Honour says that he was killed in action in France on 12th October 1917.